This week's Evidence Based Update is a discussion about cobalamin deficiency and supplementation in dogs with chronic enteropathies.

Cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency is common in dogs (reported prevalence, 6%-73%) with chronic GI disorders, also known as chronic enteropathies (CE). Hypocobalaminemia is a negative prognostic indicator and associated with an increased risk for euthanasia in dogs with CE and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). Damage to the ileal mucosal receptors, which bind to cobalamin–intrinsic factor (IF), and increased bacterial competition for nutrients in the small intestine are among the factors that contribute to decreased cobalamin available for absorption. Weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, neuropathies, immunodeficiency, and failure to thrive are among the signs of cobalamin deficiency.

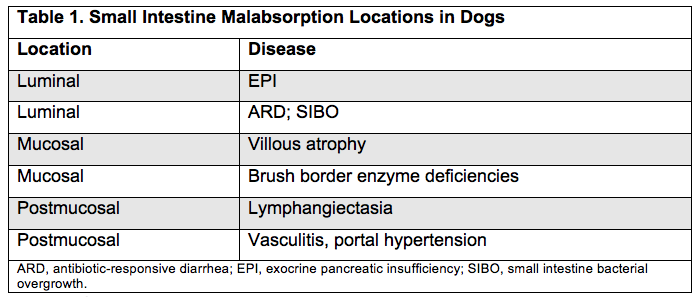

Malabsorption in the Small Intestine

Because digestion and absorption of nutrients primarily occurs in the small intestine, interference with these processes results in malabsorption syndromes, which have been studied more thoroughly in dogs than in other small animals. EPI is one such syndrome, which is characterized by impaired digestion and absorption of protein, starch, and particularly fat. In dogs, EPI is associated more often with acinar atrophy than chronic pancreatitis (which is seen in older dogs and more often in cats). Secondary antibiotic-responsive diarrhea (ARD), a common complication of canine EPI, further impairs digestion and absorption of nutrients. Table 1 shows intestinal locations and corresponding diseases associated with malabsorption.

Adapted from the Merck Veterinary Manual. Malabsorption syndromes in small animals.

In dogs, EPI often causes maldigestion, and it's important to distinguish malabsorptive disease from maldigestion, which is difficult since there are no clear differences in chemistry or hematology profiles. As many as 15% of dogs with EPI do not respond to therapy with a low-fat, low-fiber, and quality high-protein diet and empirical pancreatic enzyme replacement. Trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) assays are a standard test for EPI, but they must be species specific. Fecal proteolytic activity measurement is a more accurate test for EPI. Once digestive dysfunction and systemic, parasitic, and infection have been ruled out, malabsorption due to small-intestine disease (eg, IBD and alimentary lymphoma) is a likely reason for unexplained diarrhea and weight loss. A definitive diagnosis requires histologic examination of intestinal biopsies.

Cobalamin serum concentrations

Normal pancreatic and intestinal function is essential to maintain optimal cobalamin levels, which are necessary for amino acid, lipid, and DNA syntheses. Hence, cobalamin deficiency particularly affects the rapidly dividing bone marrow cells and enterocytes.

Dietary cobalamin binds with gastric and salivary R protein and is then released via pancreatic enzymes in the proximal small intestine to form a complex with intrinsic factor (excreted by the pancreas). This complex is subsequently absorbed by a specific carrier in the ileum. In contrast, dietary folates are absorbed by the jejunum. Both folate and cobalamin are abundant in canine and feline diets, so it's unlikely that a change in their serum concentration is due to a diet deficiency and thus it's necessary for the animal to be fasting before measuring serum levels.

Prevalences of increased serum folate (60%), decreased serum cobalamin (82%), or the combination of both (47%) have been reported in canine EPI; severely low blood levels of cobalamin have been reported in 36% of dogs with EPI. Table 2 summarizes the relationship between cobalamin and folate concentrations and EPI, small intestine disease, and small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in dogs and cats.

Source: Dossin O. Top Companion Anim Med. 2011;26(2):86-97.

Source: Dossin O. Top Companion Anim Med. 2011;26(2):86-97.

Hypocobalaminemia treatment

Fortunately, cobalamin deficiency typically responds well and safely to parenteral vitamin B12 supplementation. Dogs with severe CE (eg, IBD or protein-diminishing enteropathies) usually start with injectable cyanocobalamin 25 mcg / kg once weekly for 4-6 weeks followed by once monthly administration to maintain normal serum levels. Plumb's Veterinary Drug Handbook cites that for dogs with less severe GI-disease, cobalamin deficiency dose is based on body size—total dose of 250-1200 mcg once weekly for 6 weeks then every 14 days for 6 weeks followed 1 dose 30 days later (recheck after 30 days).

Oral vitamin B12 supplementation has been established as effective as parenteral vitamin B12 in several studies of humans with hypocobalaminemia. In addition, oral cobalamin supplementation has proved more cost effective, convenient, and comfortable than injectable cobalamin. However, until recently, the effectiveness of oral supplementation in dogs with CE has not been explored.

This week's Evidence Based Update presents data from a recently published study of dogs with signs of CE and hypocobalaminemia that were treated with oral cobalamin tablets for oral vitamin B12 supplementation. Discussion includes:

View this Evidence Based Update - Brought to you by Diamondback Drugs. (Running time 19 mins)